How To Make Your Music Louder: Four Ways from Baphometrix’s “Clip-To-Zero” Method

And why "loudness" isn't what you think it is.

How To Make Your Music Louder: Four Ways from Baphometrix’s “Clip-To-Zero” Method

Baphometrix’s CTZ (clip-to-zero method) encompasses just about everything I wanted to know about loudness when I first started producing. I don’t produce in the same way, but the lessons it’s taught me about dynamics in digital mixing were priceless in a time when I was preoccupied with this single question: “How do you make your music louder?” Baphy clearly delineates how mixing choices affect overall loudness in a way I’ve never found anywhere else. After years of asking about loudness on forums and being repeatedly told by old heads to more-or-less not worry about it, CTZ was like fresh air. I highly recommend Baphometrix’s long and hyper-detailed video series to anyone seeking in- depth lectures on how to push a digital mix louder. For anyone seeking something more concise, I will share with you my favorite bits. But first, let’s understand what CTZ is with respect to traditional methods of mixing.

CTZ represents a hard break from conventional mixing. Conventional mixing methods largely arose from the limitations of analog technology. Analog compressors, amplifiers, and mixers are known for having a wonderful “color” to them. This is a gift and a curse. It’s a gift, because the gear itself is able to impart a special warmth or tonality to the mix that purely digital workstations can only mimic at best. Analog heads love their gear for a reason. It’s also a curse, though, because this warmth is technically just noise and distortion. Analog equipment can’t be pushed very hard before the processing becomes obvious, or even ugly. Also, the signal coming into an analog mixer needs to be kept lower than it would in a digital interface. This is because a hot signal can often distort an analog channel, even if doesn’t actually clip! So to get the most out of analog dynamics processing, the conventional wisdom came to be that compressors, limiters, and the like should be applied gently, carefully, and incrementally. And even when working digitally, this approach still works wonders for the people who practice it. When you watch an engineer work this way, it’s like they begin with a mellow mix and massage it upwards into a loud and clear form, sculpting and adding color as they go.

CTZ on the other hand, is a mixing discipline for the digital age. Rather than the “color” or “warmth” sought by other mixing methods, CTZ prioritizes loudness and fidelity. It maintains the track’s cleanliness and transparency, while keeping the mix as flush against 0db as it can. This of course comes with some caveats. Firstly, it assumes that you are working completely in-the-box. It needs you to commit to sterile, digital compression. It depends on you being able to create as many tracks, sends, and groups as you want. Secondly, while it can be used on any genre, it was developed specifically for bassy EDM tracks. When DJs at live venues mix an EDM set, they don’t always perfectly gain stage the songs within it for equal loudness. This means that a dance track which sounds perfectly fine on your home speakers might end up sounding quieter and weaker than the other songs in the mix, if it happens to get thrown in the wrong way. Because of this potential variance, it’s advantageous for the EDM producers to err on the loud side when mixing their music, to ensure that it sounds powerful and exciting when the DJ plays it. This is the core focus of CTZ.

Because it departs so far from accepted mixing traditions, CTZ is often criticized to an unfair extent. Yes, it’s a little out there and it fetishizes loudness, but it also kicks ass as what it was built to. As someone who’s studied and sees the value in both worlds, I feel compelled to advocate for CTZ. Here are four things CTZ taught me that sources on conventional mixing did not.

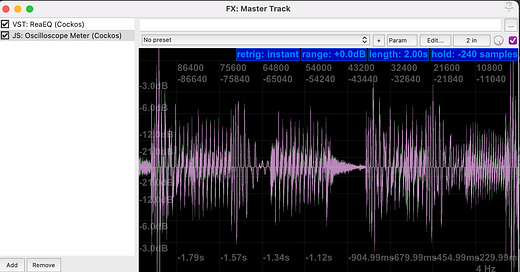

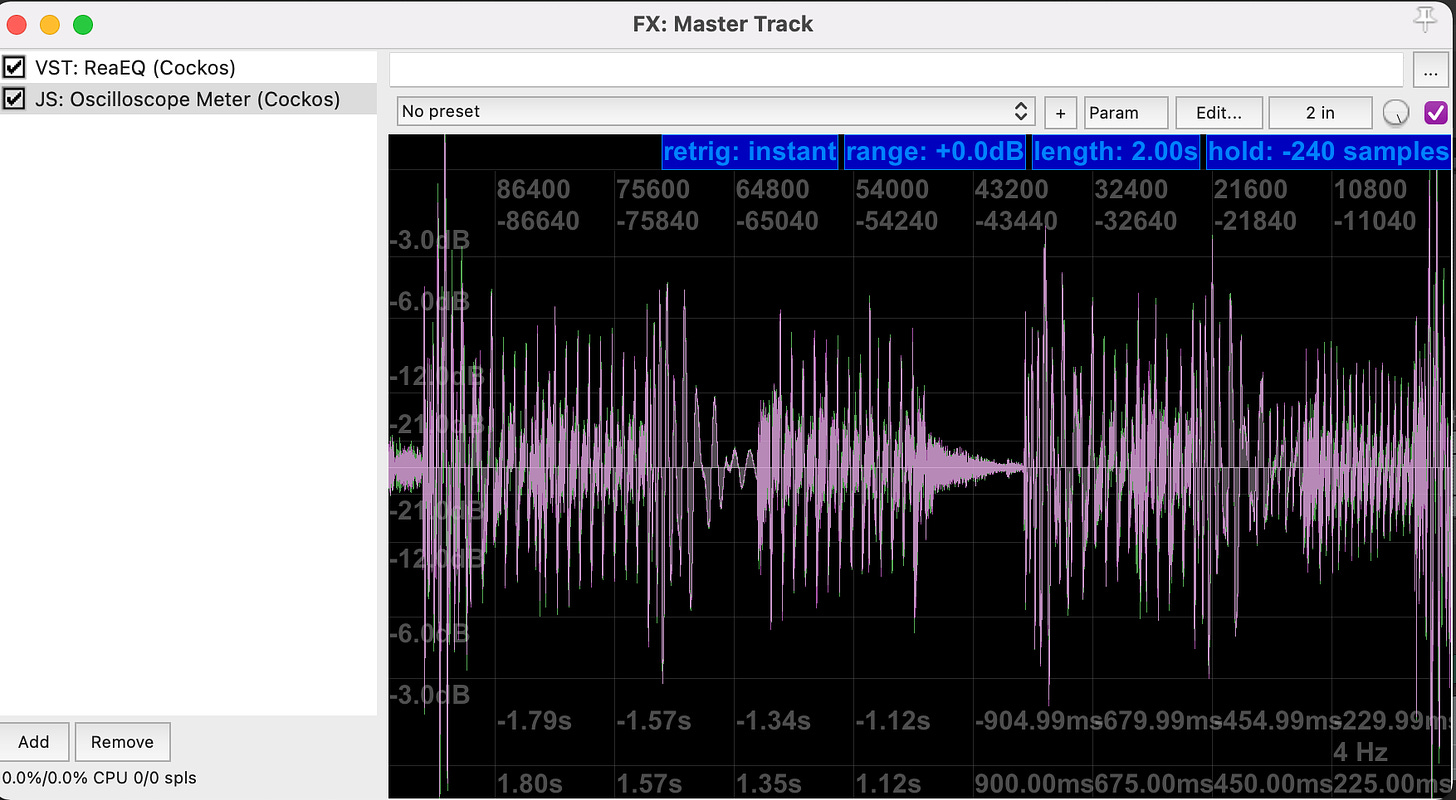

1. The Oscilloscope Will Show You How to Make Your Music Louder

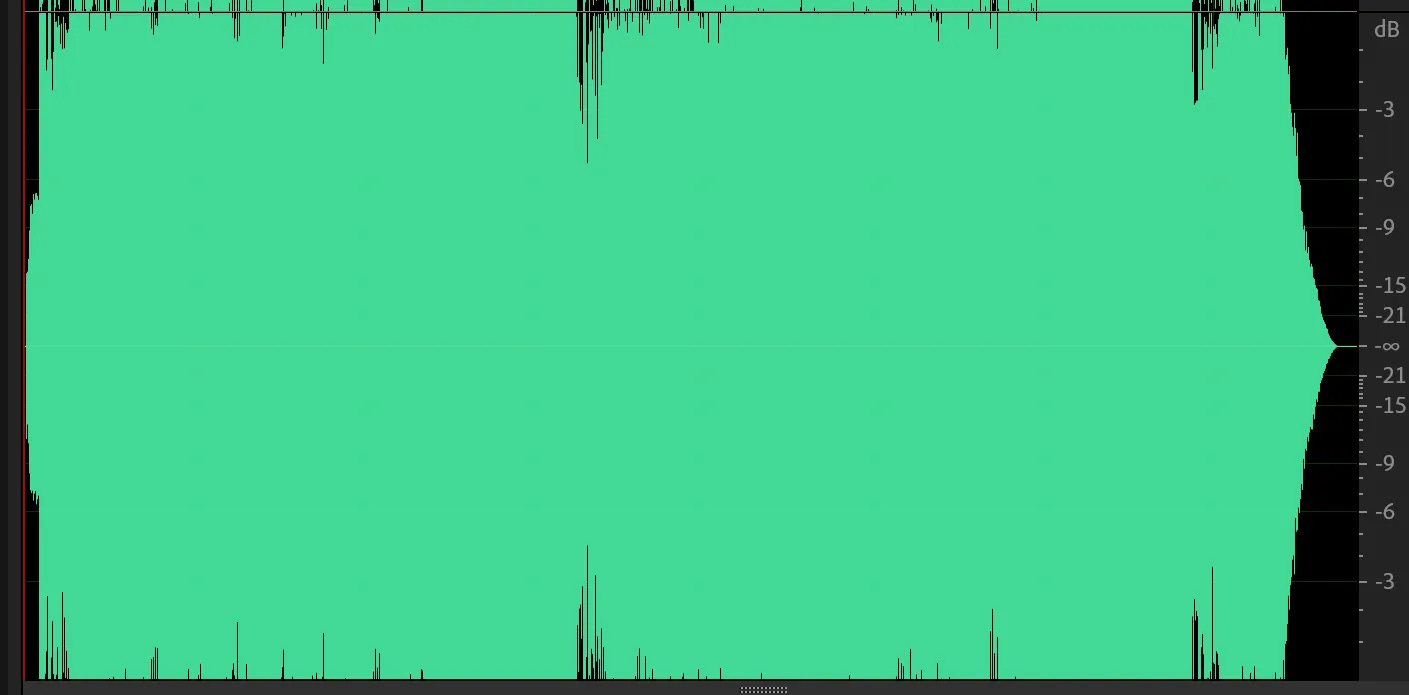

When you achieve loudness by slamming the master bus through a brick-wall limiter (as was common at the height of the loudness wars), you get a big fat loud-ass rectangular waveform. But at what cost? If you look up the first CD remasters of Michael Jackson’s pre-CD music, you’d probably be appalled at the distortion. It was ugly. When older engineers would tell me about the loudness wars, I assumed they were being hysterical. This was because I was younger than them, and had missed the worst period of what they were talking about. After all, the digital remasters I was listening to sounded fine! But in time, I found out that yes, the very first wave of CD remasters really were that crazy. It’s as if the engineers of that time were huffing paint or something. They thought all that distortion was worth it for a fat, sausage waveform.

The oscilloscope allows us to sort out this conflict between loudness and fidelity, navigating through the best of both worlds. Mixing may be done with the ears, but the oscilloscope gives the eyes important clues about about how well we’re filling the mix out. It allows us to empirically test how our mixing decisions affect the fatness of the mix’s waveform. By watching the oscilloscope as you shape elements and mix them in, you can see how your choices are contributing to the overall volume while aurally confirming that it still sounds right. That means you can visually see that you are building that sausage waveform organically, minimizing the amount of squashing the final limiter has to do.

2. Hard Clipping is Cool as Hell

When I was a total beginner, I would hear a lot about clipping. Specifically, I would hear that it was bad and you shouldn’t let it happen. And to be fair, this is good advice to give to a beginner. Clipping could cause them to mess up their recordings or gain stage in a crazy or unworkable way. The idea is that when you clip, you distort. And that’s true! But what they don’t tell you is that any kind of dynamics processing causes distortion. It turns out, a little controlled clipping on an element here or there is often

the perfect way to boost it without having to hear the compression. Compared to typical compressing or limiting, a hard clipper provides exceptionally clean output gain, acting only upon the the loudest peaks and keeping attack/release pumping to the bare minimum. Normal compression is still good for imparting musicality and shaping the envelopes of sounds, of course. But if you’ve already done that to an element and still need a way to push it hotter without changing its vibe, try a hard clipper! For tonal elements like guitar and piano, you’ll be surprised how far you can push it before you notice the distortion.

3. You Can Get Away with More Sidechain Compression and Ducking than You Think

The puzzle of how to make your music louder when it already sounds basically how it's supposed to can be frustrating. One core idea of CTZ than can be useful to us in solving this puzzle is “checkerboarding.” The idea of checkerboarding is to reduce the amount of work your final bus limiter or master limiter has to do by minimizing how much the elements overlap. You try to keep each piece clearly defined and separate, like tiles on a checkerboard. This will keep the dynamic peaks of the mix more balanced and manageable, so we can turn the mix up way more at the end. We already kind of do this when we use EQ to give elements their own little space, partitioning them by their spectral makeup. Another way to do this is by making sure big elements don’t occur at the same time, such as arranging a song to have kick drums only on every quarter-note and big bass notes only on every other eighth-note. But if you’re already past the arranging and EQ, another way to checkerboard your elements is with sidechain compression and ducking.

Imagine I didn’t have the foresight to arrange my kick and bass in the way that I described earlier. Imagine I put the bass on every eight note. Now in the mix, the bass and the kick will overlap, forming needlessly tall transients that run too hot into the final limiter. But I can separate these elements a bit by sidechaining the bass to the kick, so that it “ducks” out of the way of the kick transient as much as possible. If you set the compressor attack to hard-zero and play around with the other parameters, you’ll be surprised how much you can duck things without creating the “pumping” effect that sidechain compression is known for. It’s a great tool for precisely tucking a transient element into a steady one without relying on glue compression, which would squash them together in a less controlled, more obvious way. If you’re willing to create an intricate scheme of bus groups, ducking your steady elements around your transient ones, you can squeeze a lot of extra juice out of your mix without much impact on how it sounds. Often, when my mix is too dynamic, I will go through and duck all my major elements in this way, just short of making it noticeable. When I come back to the master bus, I find that with the overlap of elements controlled, the peaks are much milder and I have way more headroom to turn the mix up.

4. The Kick Drum Envelope Should Look Like a Dorito

Getting the kick drum right is hard. Sometimes it sounds nice and punchy when you start mixing, but by the end you’re only hearing the transient and missing the body. Or maybe you have the opposite problem— it sounds big and heavy at the beginning, but by the end you’re only hearing the body and missing the punch. Why do kick drums go off the rails at the end like that? I’ll tell you: Having the kick decay too suddenly or having the transient too high ends up overemphasizing the transient. That leaves it sounding clicky and abrupt. Having the kick decay too late or having the transient too low ends up overemphasizing the body. That makes it sound flat and weak. The sweet spot between these two decay patterns? A line drive.

In order to have the kick drum both punch through the mix and have a strong body, a good rule of thumb is to make sure the waveform looks like a Dorito. By this I mean, the initial transient should be the highest amplitude, and the body should follow a straight line from that amplitude to silence. No matter how long the decay is, try to keep it shorter than the period in between kicks, and make sure it’s shaped like a triangle. This can be accomplished by only using Dorito kicks in the first place, or forcing your kicks to conform to this shape with dynamics processing. Like all heuristics, there are exceptions to this. But for typical dance music, this will ensure that your kick drum stays punchy and dominant, while using up as little headroom as possible. And you know what extra headroom means? We can crank the volume higher later on.

Criticisms of CTZ, and why the question “How To Make Your Music Louder” is hard to get a straight answer to.

Critics of this particular method and the general pursuit of loudness are right about one thing: the loudness war is over. Direct competition of music recordings on the basis of loudness is a holdover from a previous era. Let’s talk about that era. For a brief period at the zenith of CD’s and mp3 files, there was a special set of circumstances that gave audio engineers both the ability and the motive to push tracks to incredible loudnesses, often at the expense of quality and fidelity. The ability to do so came from the introduction of computers to analog studios. By incorporating DAWs and computer plug-ins in their workflow, music makers were no longer bound by the limitation of analog production. They gained access to digital gain and digital compression— harder and cleaner methods of increasing loudness than they had ever imagined possible.

The motive to crank it came from the forms of popular music at the time. CD players and iPods did not normalize the music played by its perceived loudness. If they normalized the levels at all, it was by the average volumes of the tracks. Volume is related to loudness, but differs in that it only represent the electric signal needed to produce the sound— not how loud it feels to our ears! This meant that in those days, the loudness of a finished track was entirely up to the people who made it. There was no platform to turn the music up or down for the end listener, nor any penalty for a track for being too loud. Songs and albums were exactly as loud to the listener as the engineers printed them to be. And as you probably already know, listeners are generally biased to favor louder versions of the same sound.

It’s common sense when you think about it. If you’re a pop, rock, or hip-hop musician at this time in history, your audience is rapidly switching between your CDs and their other CDs in the disc player. They’re shuffling your raw mp3 files together with all the other ones in their iPod. Wouldn’t you want your track to feel bigger and stronger than the others? Wouldn’t you want it to stand out?

One (one) good thing about the streaming services which replaced those disc players and iPods, such as Spotify and YouTube, is that they normalize audio based on loudness. They do this by weighting the volume of a track against the distribution of its signal across the frequency spectrum, giving more weight to the frequencies we are more sensitive to. This ensures that almost everything, respective of genre and tone, sits around the same level. Today, we still have the ability to to crank audio to crazy- high levels. But because loudness normalization has become standard, pushing the loudness of a track past the target loudness platforms normalize for no longer makes it sound any louder to the end user. The incentive to crank it is no longer there.

But even now that loudness normalization is ubiquitous, it’s still important understand and have control over loudness. Even platforms who normalize this way still have optimal loudness ranges, within which tracks are sufficiently loud without being affected much by the normalization. The target for streaming is around -16 Lufs to -12Lufs. Plus, in other audio media such as audiobooks and certain podcast platforms, hard loudness requirements are common. So it’s definitely still important to know how to increase the loudness of your mix in a controlled, precise way. You may even need to cool your mix down, reversing CTZ-thought to precisely add dynamics rather than compress them out.

It’s for these reasons that I wanted to synthesize CTZ with conventional mixing, yielding four simple heuristics for managing loudness within a digital mix. But always remember, loudness is a perceptual quality to our ears— not a number on a meter. LUFS and waveforms, as useful as they are, are merely tools to help us understand what we’re hearing. Ultimately, the best way to sound loud is to produce and work with material that sounds loud in the first place. Beyond that, it comes down to processing. So whichever side of the CTZ debate you’re on, these four distillations are fantastic tools to get the loudness and dynamics of your mix exactly where you want them.

By the way, I’m Riley! For more resources on music production, audio engineering, or digital media in general, visit me at my website, Big Fat Mix and Master